Tudor Acts

Where the Law and Art Meet

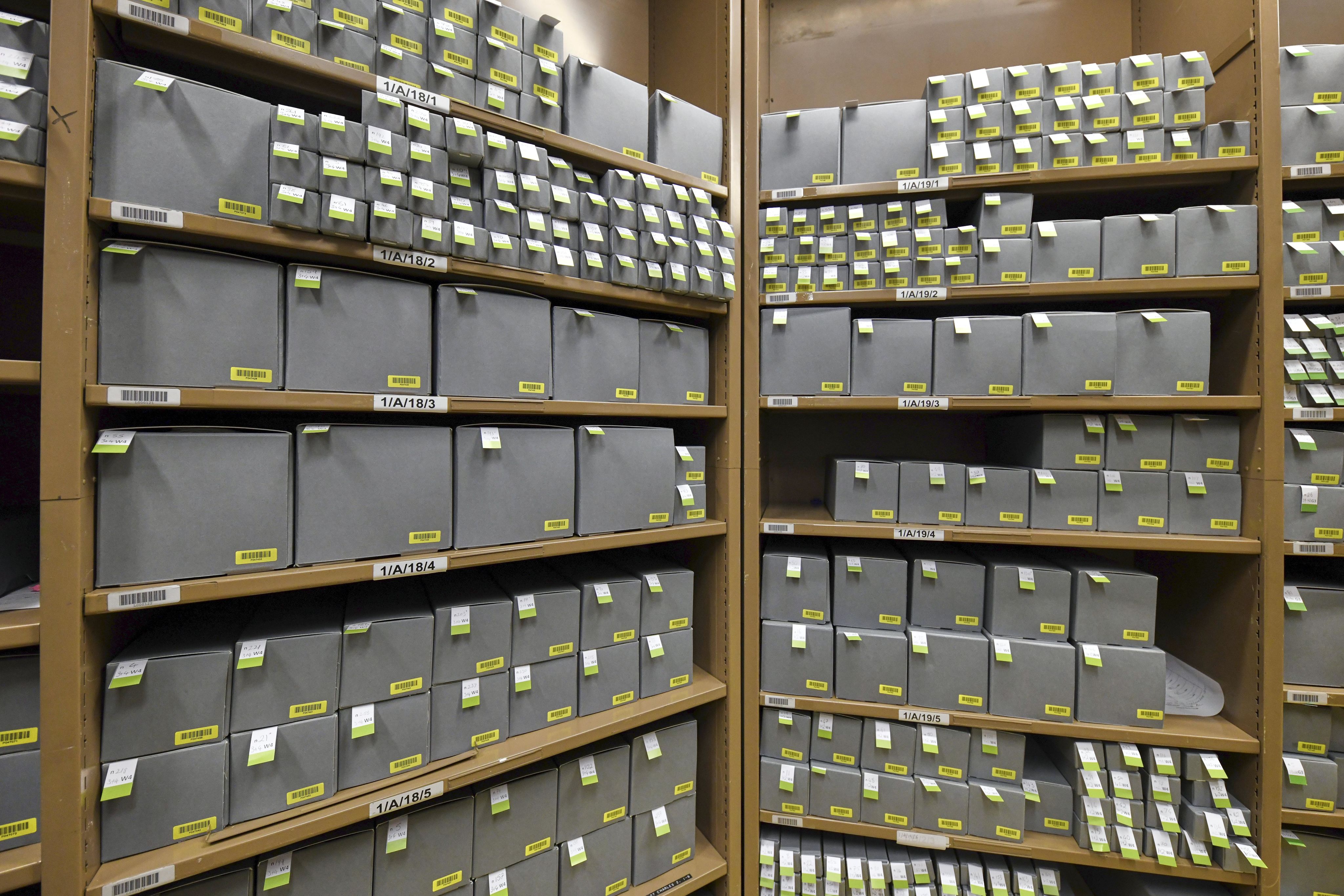

In January 2018 the Pack and Track Team [PAT] (followed, in October 2021, by the Prepare and Move Project [PAM]) began the task of preparing the Archives collection for a move off-site. The work has several streams including barcoding, cataloguing, and collection care. Part of the Projects collection care role has been cleaning and boxing acts. This has had two phases, the first phase was to clean and box the Modern Acts, which was completed in 2019 (for more information on Acts of Parliament see our blogs The Parliamentary Archives Jargon Buster: Acts of Parliament and When Records Began- A Plotted History of the Parliamentary Archives Firsts). Then the PAT Team moved onto cleaning and boxing of the Rolled Acts from 2019.

There are a number of practical reasons for boxing acts individually, over and above making it easier to move when the Archive relocates. It creates more stable conditions in the interior of the box and therefore will allow more consistency even if relative humidity and temperature in the room are controlled. It also protects the act from damage by other acts stacked around it.

As before boxing, rolled acts were stacked on shelves, one on top of the other, meaning those at the bottom risked getting damaged from the weight of those above. There is also the risk of abrasion as acts rub against each other, and any dust that accrues on their surfaces becomes an abrasive when they are retrieved for readers in our Search Room. That is also why we cleaned the acts, as general atmospheric dust had built up over the years, even with filters in our repository.

For these reasons cleaning and boxing the acts was deemed a sound preventative measure. This cleaning and boxing process has also allowed us to audit all the acts, letting The Preservation and Access Collection Care Team know if any need further attention.

Hidden surprises

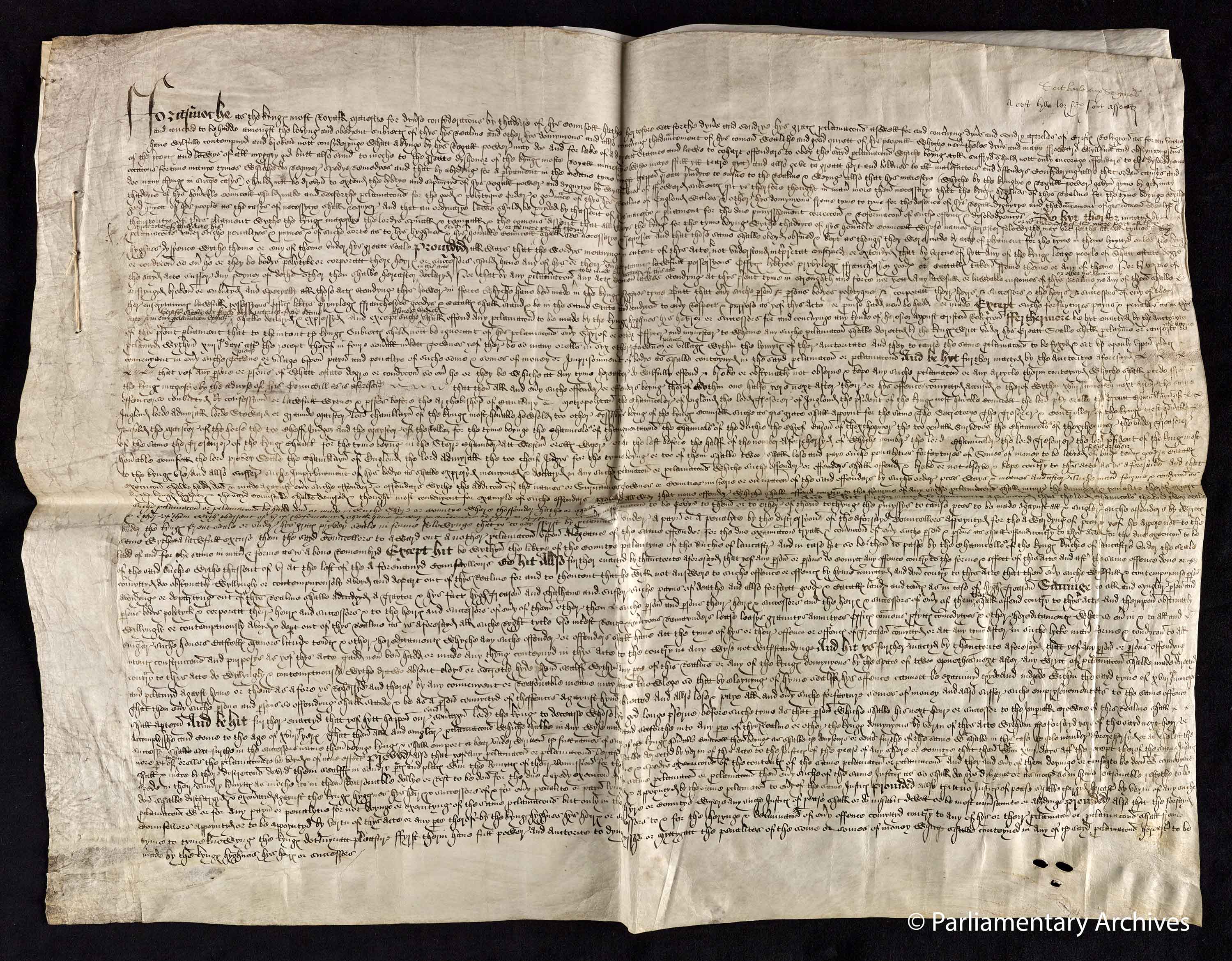

As we are packing all the acts, the flat acts also needed to be assessed. These flat acts were from the Tudor period (1485-1603) and had been boxed together previously in Regnal Years. A Regnal Year in this context is the year of a monarch’s reign from the moment of accession to the throne to the end of a Parliamentary Session. Therefore, some years will run, 1, 2, 3…, while others will be 4&5, 5&6, 6&7… if the Regnal and Parliamentary Year do not match. An example of this is the Act pictured (HL/PO/PU/1/1539/31H8n8), which shows it was passed in the 31st year of Henry VIII’s reign, and was the 8th act passed that year (the “n8” part).

Incidentally, this is how all acts are grouped, the only difference is that these early years are small enough that they can be housed together in one bespoke box, while boxing of rolled acts puts each act in individual boxes.

Artistic flourishes

It was a wonderful surprise to see that some scribes let their artistic nature run wild, adorning the act they were working on with elaborations. The following acts show the variety of work done over the 16th century and is not meant to be a timeline or evolution of handwriting styles.

Nevertheless, some of the acts are fairly subdued, slightly enhancing the first letter of the act, or having a capital only a little bigger than the rest of the act as is seen in Kings Proclamations from Henry VIII in 1539.

Others have some embellishment, that shows a nod towards the document being important, and worth the time to embellish it as can be seen in the 1539 Lady Rochefords Jointure.

In these first two examples it can be seen how much variation there is over the same year, and when looking across multiple years more unusual elaborations can be found. Therefore, it is not surprising to see that there are others that were much more ornate.

Moving from these comparatively basic ornamentations to an Act for Assuring the Manor of Birmingham to the King where there is a middle ground of enhancement with a lot more pen strokes used to make Celtic knot style design.

While this looks complicated, they are of a fairly simple composition compared to what we will see later. This is not to diminish the skill of the scribe but to note the level of complexity that we are now going to move onto.

A further example of this middle ground can be seen in An Act Authorising the Kings Highness to make Bishops by his Letters Patent.

This looks very ornate but also has a seeming graceful simplicity to it. In this Act, there are fewer strokes than in the previous act, but it has a beautiful elegance to it.

We'll now take a look at more creative designs on our acts.

The Restitution of the First Fruits Act 1536 shows a blend of straightforward embellishment, using pen strokes, with an added flourish of a zephyr (a puff or breath of wind) coming out of the letter at the top right. This Act has a similar feel to some of the most ornate initial letters we will come across.

The ornamentation really comes to the fore in the next two acts; firstly an Act ratifying an Award made by the King 1536.

As well as the elaborate leaf-like structure of the first letter you can also see Henry VIII's signature next to the embellishment and above the first line of the Act.

An Act for the Earl of Oxford 1551 shows more elaboration than we have seen so far.

This Act has a particularly unusual detail as it has writing within the first letter. In the scrollwork, there is the Latin phrase Vivat Rex, translated as “Long Live the King”.

You can also see the signature of Edward VI (Henry VIII's son) along the top of the Act.

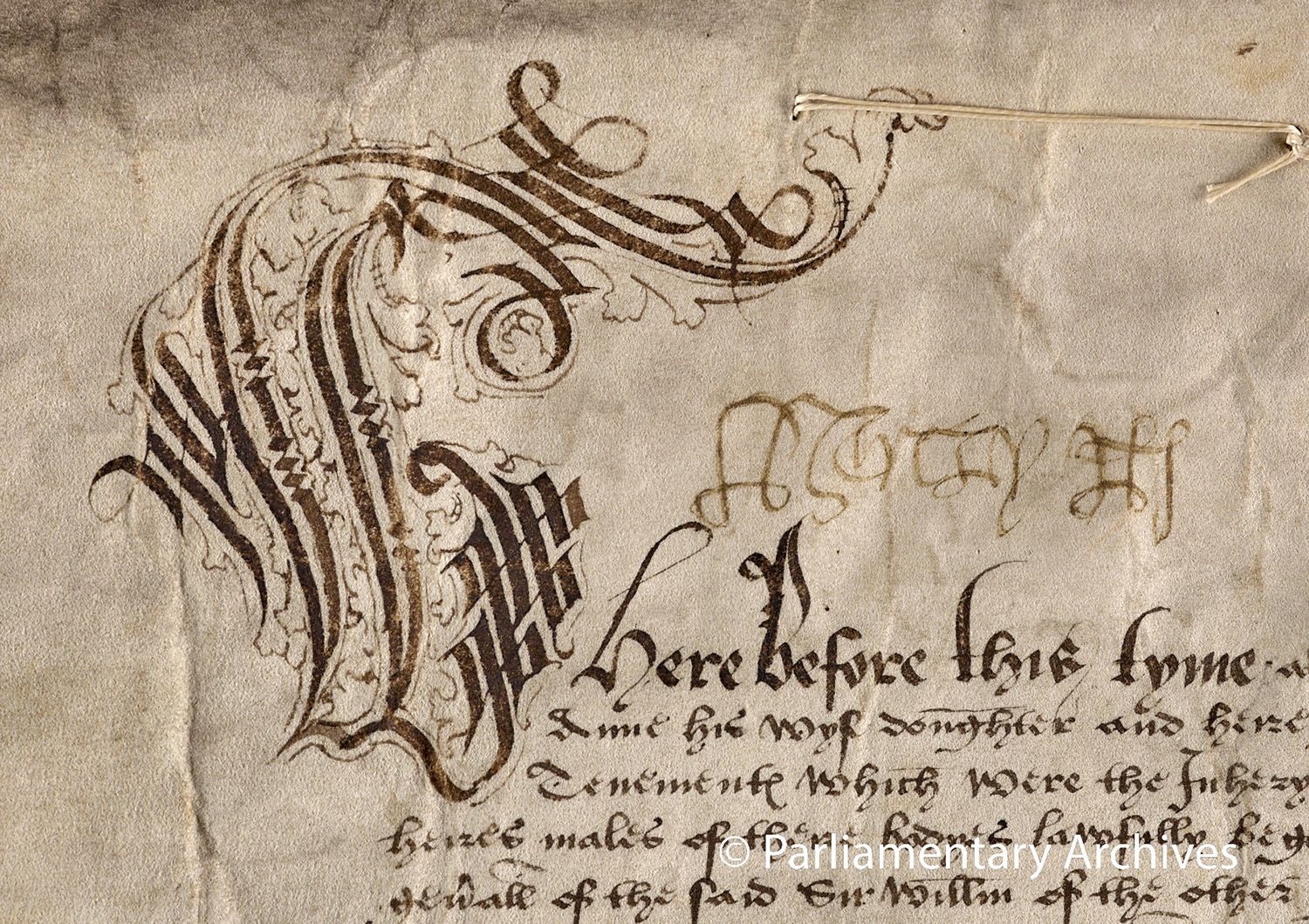

We are now going to look at an Act passed during the reign of Elizabeth I, the last monarch of the Tudor period. The Act for the Restitution in Blood of Anthony Mayne 1580 has a couple of very noticeable focal points.

First, we have a wonderfully fluid signature, which is far bigger than signatures from the other monarchs of this period.

Probably though the most noticeable part is the most ornate capital that was found during our audit. Here are all the embellishments (bar Latin phrases) we have seen to this point. While the Act itself is not particularly big, this detail is almost the entire Act as can be seen looking at the size of the rest of the writing.

The capital is not the only elaboration in this Act, as it also has wonderful ornamentation across the letters of the first few words, making a much more embellished final piece. This added level of ornamentation will lead us nicely onto some of the more unusual acts found during the surveys.

Another curiosity that perfectly blends what we have already seen, with what is to come, was found in An Act for the making of a Chappel in Carmarthenshire 1558.

This Act seems to move from pure elaboration to something a little more creative. At first, this Act looks like the previous acts, with its elaborations over the letters of the first few words. However, much more attention has been paid to the space around the capital, with illustrations of flowers and the addition of a border, than we have seen before, showing a much more creative outpouring and something that in many ways would be more expected in a woodcut printed document than a manuscript one.

The final Acts that we will look at will focus on the most unusual embellishments found in this survey. I thought I would start this by looking at two acts that you might need some imagination to see. The first is An Act Concerning William Skeffington 1571.

This piece starts to really show the breadth of unusual embellishment. In this detail, I at least feel there could be a creature designed into the first capital letter. On the left, there is a head, with a tongue poking out, its wings added across the top, the tail at the end of the elaboration and the legs being formed with the shafts of the letter.

While the second Act for Assuring Lands to Thomas Jermyn 1536, may just be me seeing things, but seems to be a ship in full sail (moving left to right) with an enlarged prow and stern. There is even a line trailing off the stern, creating a ripple where it enters the water. Even if this may be stretching things somewhat it does further show the variety of elaborations and creativity.

The last two acts that we will be viewing really show the individualism of the scribes of the 16th Century.

One of the most unusual acts I came across was An Act for the Submission of the Clergy to the Kings Majesty 1533.

In this Act, while the first letter is not particularly ornate in itself, the trailing flourish most definitely is. You may need a second look, but look closely along the flourish and there are a few notes scored in makeshift staves. I am not sure if this is a playable tune (at least not on the stave structure we know today), but I wonder what the scribe who wrote this was imagining when he noted it down?

The final Act we are going to look at, An Act for the Punishment of Heresy 1533 really shows individuality.

We can see a rather nice piece of calligraphy, but for whatever reason, the scribe didn’t stop there. Was it the end of the day and their mind was wandering, or a moment of rebellion? We will never know. Whatever the reason here is a beautifully realised profile of a face. The detail around the nose and lips along with the look around the eyes seem to point to this being a real person, rather than an imaginary doodle. Although we will never find out I do wonder if this was a fellow scribe, a friend or family member, or maybe a self-portrait of the scribe themselves.

I hope you have enjoyed looking through some of our more unusual acts. While those presented are just a small selection of acts that had that extra flourish on them, I hope it highlights the personality and individualism of the people who created them almost 500 years ago.

You can learn more about our collections from our Twitter @UKParlArchives and Facebook.

We have a selection of online displays including:

Succession: Queens that ruled

Spectacle & Ceremony: Coronation Banquets & Westminster Hall

Parliament & The Falklands Conflict

You can find out more about the Parliamentary Archives Relocation Project on the Parliament's website.