Minority communities have often been overlooked in Northern Ireland

We highlight four key issues that minority ethnic groups, migrant communities, and representatives told us need to be addressed in Northern Ireland.

The 2011 Census revealed Northern Ireland to be the least ethnically diverse nation of the United Kingdom.

Upcoming figures from the 2021 Census are widely expected to show an increase in the ethnic diversity of the population since then. However, public and political spheres have so far largely failed to reflect the growing diversity of Northern Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee launched an inquiry in April 2021 into the experiences of minority ethnic and migrant people in Northern Ireland.

We heard from and spoke with organisations and individuals representing or working with minority ethnic and migrant communities in Northern Ireland; we also met informally with groups during two visits to Belfast. We are very grateful to everyone who contributed their expertise and experiences to our inquiry.

We are mindful that many of the issues explored in this inquiry relate to matters devolved to the Northern Ireland Executive and that our committee's usual scrutiny is reserved for the UK Government and the Northern Ireland Office.

However many important issues were raised with us on the experiences of minority ethnic and migrant people in Northern Ireland. These issues have been either largely overlooked or under-addressed and it is important that the incoming Executive and Assembly should seek to address them without further delay.

Here are four of those key issues identified during our inquiry.

“Green and Orange” politics

and representation of minority ethnic identities

The politics of "Green and Orange"

Several witnesses to our inquiry stated that minority ethnic communities have often been “overlooked” in politics and policymaking in Northern Ireland.

The architecture of the political system set up under the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement requires the two main communities in Northern Ireland, Unionist and Nationalist, to share power in government.

We heard from groups that there was a perceived priority given to “Green and Orange” issues and the delicate challenge of maintaining peace in line with the Agreement. This can squeeze out attention for other important matters in society and can marginalise minority ethnic and migrant communities, often seen as “other”.

"We are so caught up in orange and green issues and trying to maintain peace in line with the Good Friday Agreement that the focus does not spread out over other issues in our society."

Lack of representation in public life

The lack of priority and time given to many issues affecting minority ethnic communities correlates with a visible lack of representation of minority ethnic identities in public life.

Figures from 2017/18 also show that 24 out of 942 of public appointment applications were made by minority ethnic people. In 2019 only one councillor was of a recorded minority ethnic background, out of a total of 462.

"...the lack of minority ethnic leaders has contributed immensely to the lack of focus or prioritisation of racial equality or support for minority ethnic people."

The need for better representation is not confined to the political sphere. Minority ethnic police officers "sit at 0.5% of the workforce" within the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), while officials from the Northern Ireland Civil Service also acknowledged that they have more to do to improve the ethnic diversity of their workforce.

We urge organisations and political parties to take steps to encourage representation of minority ethnic voices within their own institutions - so that politics and civil society become more diverse and better reflect Northern Ireland society today.

Absence of ethnic monitoring data

Lack of data makes some communities 'invisible'

Minority ethnic communities may also be largely invisible to policymakers due to the lack of ethnic monitoring and data on the population. This concern was identified frequently and, in this regard, Northern Ireland trails behind the rest of the UK.

"...It would be useful to have ethnic monitoring, and it is just not there. We have the Catholic/Protestant/ other split in the monitoring, and that is it."

Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 introduced a statutory duty on public authorities to carry out their functions while promoting equality of opportunity and good relations in respect of a range of categories outlined in the Act, including race.

However, Geraldine McGahey OBE told us that as Northern Ireland does not currently have any form of ethnic monitoring, "all policy development to this date has been flawed, in that it has not been built on robust data".

Liz Griffith, a policy officer at Law Centre NI, said that even immigration data for Northern Ireland was, for a long time, impossible to extract as Scotland and Northern Ireland were considered a single immigration region.

We urge The Executive Office to implement wider monitoring as a matter of priority once a new Executive is formed.

Hate crime in Northern Ireland

Racially motivated hate crimes have increased in Northern Ireland

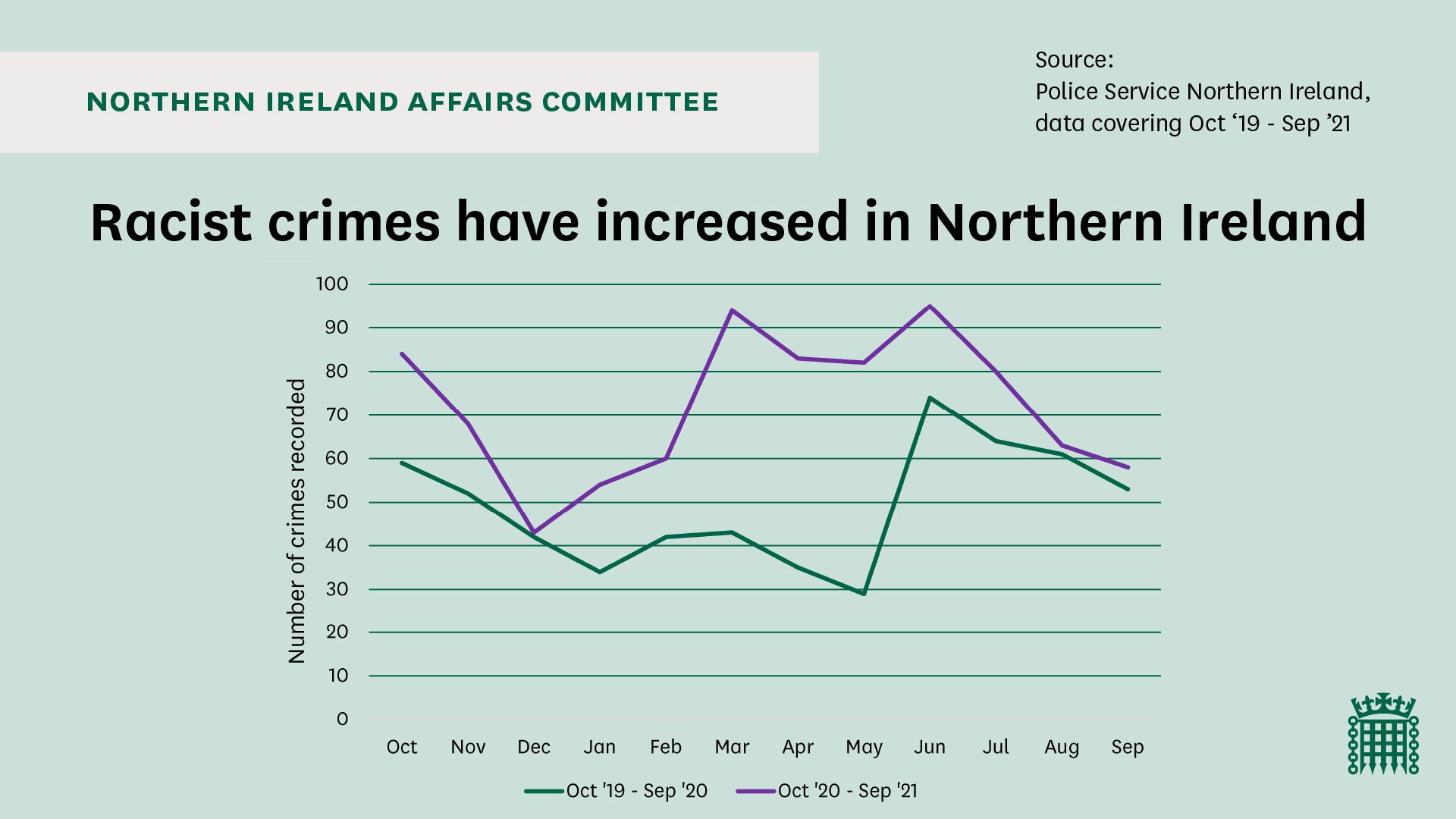

PSNI statistics show that racially-motivated hate crimes increased in the years from October 2019 to September 2021.

Although figures still remain lower than the peak of 2014/15, there were a higher number of racially-motivated crimes reported (41%) than sectarian crimes(38%) in the year to September 2021.

This statistic is more significant when considered in relation to the small proportion of the population from black and minority ethnic backgrounds in Northern Ireland.

The PSNI said there is also strong evidence to suggest that many other incidents go unreported to the police, so we don't know the full scale of the problem.

“They [politicians] need to urgently address the matter, urgently respond to the abuse that ethnic minority people are facing and give us some sort of protection in respect of that.”

The contrast in Northern Ireland hate crime legislation compared with the rest of the UK was also raised with us.

A recent review of hate crime legislation in Northern Ireland was published in December 2020. This recommended (amongst other things) amending the way in which, and at what stage, hate crime is dealt with under the law.

The Department of Justice intend to introduce the hate crime Bill by autumn 2023, with the final stage of the Bill completed in spring 2024.

Legislation needs strengthening to ensure better protection is provided for victims of hate crime. We therefore welcome the launch of a public consultation ahead of a new Hate Crime Bill, which is due to be introduced in the next NI Assembly mandate.

The experiences of refugees and the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme

NI refugee resettlement schemes

Since 2015, Northern Ireland has welcomed over 1,800 people who have been resettled under the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS).

There was praise for the consortium model adopted by the Executive in response to the Syrian scheme, which enabled joint working between the public and voluntary sectors.

"In some areas, the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive have shown a real willingness to take an innovative approach with [...] the consortium model that has been delivered around the Syrian VPR scheme in Northern Ireland."

However, we also heard about mixed experiences regarding access to and provision of services for families once they had arrived. Not all people coming to Northern Ireland arrive through managed schemes such as the VPRS and one key concern was that many services for refugees are often "Belfast-centric" and inaccessible to those living in rural settings.

"It is not just about getting the physical house. It is also about what is in the local community [...] Getting an interpreter there was the cost of somebody driving from Belfast, for example, to Newry or up to Derry/Londonderry."

Other issues raised in relation to the experiences of refugees included housing provision, access to healthcare services and children's needs. The NI Executive has since published a draft refugee integration strategy, though it was the only part of the UK without such a strategy until now.

We are pleased to hear that Northern Ireland will soon join other parts of the UK in having a refugee integration strategy. We ask that all the issues we have cited in our report be addressed as part of the final strategy, and done so at pace.

What happens now?

We published a report with our findings on 9 March 2022

The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee's direct responsibility is to scrutinise the work of the UK Government and Northern Ireland Office, rather than The Executive Office of the Northern Ireland Executive, but many of the findings of our report bear upon the role and responsibilities of the Executive.

For this reason, we would be very grateful if The Executive Office could seek to respond to this report in three months' time, setting out:

- its general response to the findings and the evidence received during our inquiry

- an update on recent progress made by the department in this area, specifically on the implementation of the actions contained within the 2015 Racial Equality Strategy.

Detailed information from our inquiry can be found on our website.

If you’re interested in our work, you can find out more on the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee website. You can also follow our work on Twitter.

Cover image credit: Ty via Flickr