Influencers: lights, camera, inaction?

'Influencers' are reshaping the media landscape. Now it's time to reshape the influencer industry's regulations.

Influencers have disrupted the media landscape

The rise of influencer culture is increasingly reshaping traditional and digital media, with many prominent influencers gaining large and devoted audiences through uploading content onto social media platforms.

As such, influencer marketing is now estimated to be a $13.6 billion industry worldwide. However, the rapid expansion of this marketplace, both in scale and in technical innovation, has outpaced the capabilities of UK advertising regulation.

We note that behind the perceived glamour, this is a challenging career beset by diversity issues, pay disparities, and a pervasive lack of employment support and protection.

Despite the significant returns that influencer culture brings to the UK economy, the industry has not yet been given serious consideration by Government. Influencer culture is a rapidly expanding subsection of the UK's vibrant creative industries, and the UK has an opportunity to be a world leader in this area.

In our report we consider the benefits and challenges of this new industry and identify the gaps in regulations that need to be addressed. This also includes new, and now key, questions that arise on protecting children as both creators and consumers of influencer culture.

What is the impact of social media influencers on UK culture?

What is an 'influencer'?

Influencer culture is broadly misunderstood and hard to define

Our inquiry sought to find out how exactly an influencer could be defined. However, as a growing phenomenon, we were told that the term was changing and that defining the term ‘influencer’ is challenging.

There is no established basis in law and little consensus among industry stakeholders. As such, broader terms such as "content creator" or platform specific "YouTuber", "TikToker" or "Twitch streamer" are used interchangeably.

From evidence to our inquiry, the primary focus of most definitions was the commercial element of influencing. Consumerism and advertising are often linked to influencing, since most influencers provide their content free to platform users and must therefore find ways to generate revenue from their work.

“If being an influencer is not formally defined and rules and regulations guide future operations, then society as a whole is poised to suffer through nefarious and unscrupulous practices”.

Despite these complexities, defining what constitutes an influencer and influencer culture is a necessary step to effectively enforce rules and regulations.

Our definitions of influencers and influencer culture

For the purposes of our report, we have defined 'influencers' and 'influencer culture' as follows:

Influencers:

An influencer is an individual content creator who builds trusting relationships with audiences and creates both commercial and non-commercial social media content across topics and genres.

Influencer culture:

The social phenomenon of individual internet users developing an online community over which they exert commercial and non-commercial influence.

Five issues around influencer culture

1. It's not always glamorous behind the camera

Being an influencer is becoming an ever more popular career choice. One reason is due to the perception of influencing as a glamourous job, often involving paid-for holidays and free gifts. However, this is often a façade that hides long hours and hard work.

Many influencers who we spoke to also said they had experienced extreme abuse and trolling. Some felt they had put themselves forward for this by being in the public eye, and it appeared to be a bigger problem for women than it was for men. This abuse may also be exacerbated by the negative public perception of influencing as a career.

2. There needs to be transparency around influencer pay and employment

Whilst influencing as a career has seen a surge in popularity, our inquiry heard that it is still very challenging to make a living in the industry. For many influencers, building their community organically often means working for free for the first few years. A small number of influencers can take the lion's share of well-paid work, while many others struggle to make a living.

The relatively young influencer industry also suffers from a lack of payment transparency. This has led to pay gaps between different demographic groups, most notably impacting influencers from minority ethnic backgrounds. A lack of standardised pricing for work has made it easy for influencers to undercut each other, and brands to underpay.

3. Advertising regulation needs to catch up with the changing digital landscape

The rapid growth of the influencer industry has exposed gaps in advertising regulations, and the huge volume of content appearing across multiple platforms makes monitoring advertising standards difficult. We heard from the Competition and Markets Authority that compliance with the rules is still “unacceptably low”.

Messaging about the rules around advertising and transparency also lacks clarity. Many influencers, especially new entrants to the market who may lack support, are still unaware of their obligations.

4. Influencer advertising should be made clearer to children

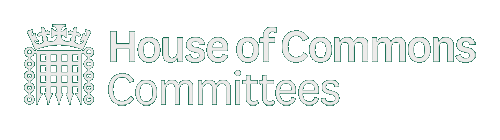

It’s estimated that one in three internet users are children and when it comes to advertising and influence, they can be particularly vulnerable. Children are also increasingly following multiple influencers online.

Whilst influencer culture can bring benefits to children by amplifying diverse voices and building communities, the close bond they can make with online figures leaves them at risk of exploitation.

Influencers appear to offer a personal relationship which can be used for both positive and commercial messaging. There is often a financial incentive for influencers to post extreme content, and children may be more susceptible to the harms that can arise from this.

Influencers can also promote idealised images of their bodies and lifestyles which can make young people feel a pressure to be perfect. This in turn can be very damaging for their mental health. Currently, there isn’t enough regulation to protect them from this.

5. Child influencers should be registered as 'working children' and protected accordingly

Children are also quickly becoming some of the most popular and successful influencers in the market. They can be part of their parents’ platforms or generate their own content, for example through gaming channels. Sometimes these children can build such big audiences and revenue opportunities that they become the primary income streams for their families.

The UK child performance regulations do not currently apply to user generated content, so child influencers are not afforded the same protections around the pay and conditions of their work as other children in the entertainment industry.

At present, there a very few ways to regulate how children are participating in the influencer community, and the impact this may have on them, including on their consent and privacy.

Perspectives

We heard from different groups with different viewpoints on influencing and how it works. Here are some of these perspectives, as told to us during our evidence sessions.

Influencers

Amy Hart. Content creator, activist and former Love Island contestant

Amy Hart. Content creator, activist and former Love Island contestant

“People need to realise that it is a real job, and I didn’t realise how hard it was to be an influencer until I was one. I used to think it wasn’t a proper job either, and it really is, especially being a content creator.”

Nicole Ocran. Co-Founder, The Creator Union

Nicole Ocran. Co-Founder, The Creator Union

“We have noticed that black and brown, LGBTQIA, disabled creators are the ones who lose out the most when it comes to working in this space.”

Em Sheldon. Influencer

Em Sheldon. Influencer

“It is 24/7. Growing up, I thought my mum worked long hours and here I am working triple time. I feel like I am a hamster on a wheel and if I am not constantly replying to people or creating content I am going to get left behind.”

Sergei Urban. Parenting influencer at The Dad Lab

Sergei Urban. Parenting influencer at The Dad Lab

“I post myself, so I know that if something is wrong or if some more information is shared than I want to, I do not upload the content.”

Advertisers, agencies, academics and platforms

Ed Magee. Chair of the National Network for Child Employment & Entertainment

Ed Magee. Chair of the National Network for Child Employment & Entertainment

“Certainly, we are concerned about the impact [the influencer industry] may be having on children now but also in the future. We want to make sure that those children are protected in the same way they would be if it was the entertainment industry.”

Amy Bryant-Jeffries. Head of Partnerships, Gleam Futures

Amy Bryant-Jeffries. Head of Partnerships, Gleam Futures

“There needs to be a bit more clarity on those different forms of [advertising] partnerships and how they should be disclosed…there is not one universal way and that means it is sometimes unclear.”

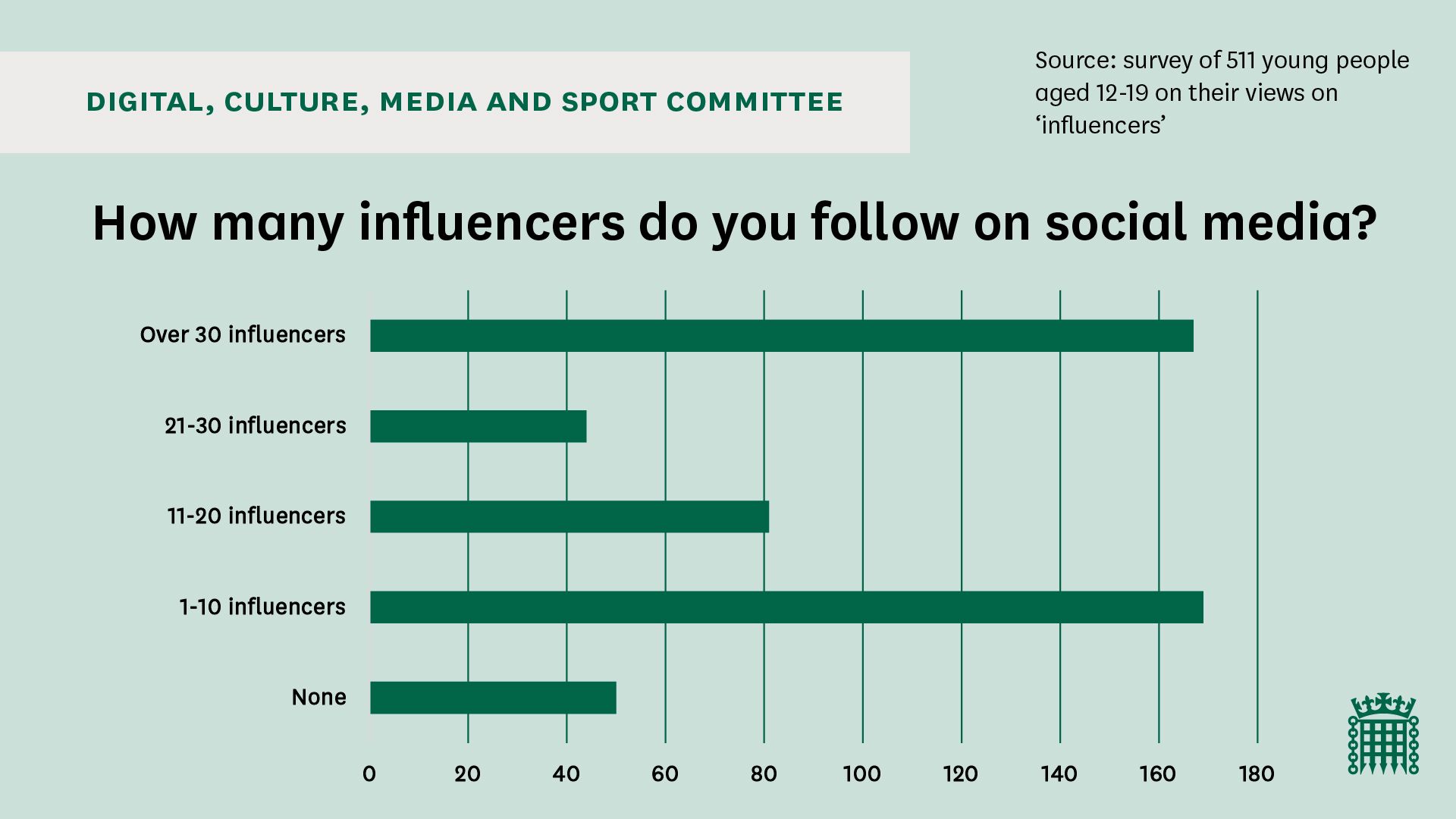

Professor Sonia Livingstone. Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics

Professor Sonia Livingstone. Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics

“At the moment, the entire content landscape is dictated by profit and brand or platform decisions, and it is not in the interests of children.”

Tom Gault. UK and Northern Europe Public Policy Lead, Instagram

Tom Gault, UK and Northern Europe Public Policy Lead, Instagram

“People can feel pressured to maintain their audience. We do not want that to be the case. We want them to be in it for the long term and for them to monetise where they feel that is beneficial to them—where it may even create an entire business out of the work that they are doing.”

Five recommendations

We recommend a broad range of legislation reforms and regulation changes to deal with these issues.

Here are our top five recommendations.

1.Conduct an industry review

The Government should conduct or commission a market review into the influencer ecosystem to address the institutional knowledge gap around this rapidly expanding industry.

2.Develop a code of conduct

The Government should commission an industry partner to develop a code of conduct for the influencer marketing industry alongside relevant stakeholders and promote this code as an example of best practice for deals between influencers and brands or talent agencies.

3. Give the Advertising Standards Agency more powers

The Government should give the Advertising Standards Authority statutory powers to enforce the Code of Non-broadcast Advertising and Direct & Promotional Marketing

(CAP Code).

4.Mandatory advertising disclosure when targeting ads to children

The Advertising Standards Authority should update the CAP Code to enhance the disclosure requirements for ads targeted to children or an audience composed predominantly of children.

5. Address child labour legislation

The Government should develop new legislation to address the gaps in UK labour legislation that are leaving child influencers vulnerable to exploitation.

What happens now?

We have made these recommendations to the Government.

The Government now has two months to respond to our report.

Our report, 'Influencer culture: Lights, camera, inaction?', was published on 9 May 2022.

Detailed information from our inquiry can be found on our website.

If you’re interested in our work, you can find out more on the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee website. You can also follow our work on Twitter and use the hashtag #InfluencersInquiry for updates and to join the conversation.

The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is responsible for scrutinising the work of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies, including the BBC.

Cover image credit: Timek Life via Unsplash